The Border Runs Through the Tongue: Three Versions of The Double Man

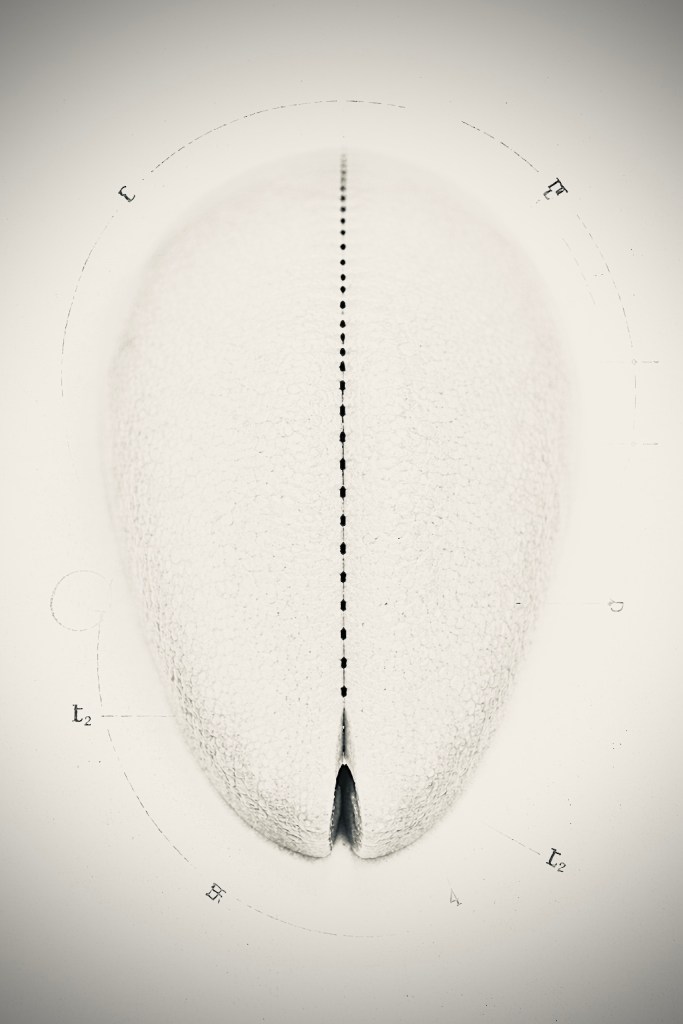

It seems fitting that there are at least two versions of this poem by Zafer Şenocak, originally published in 1993 without a title. One version later appears under the name Doppelmann (The Double Man in English translation), while another English translation circulates online, unverifiable but compelling in its phrasing. The poem itself is doubled, halved, and reassembled — and in doing so, it embodies the conditions it describes.

Below are three English versions of the same poem.

First version (untitled):

I have my feet on two planets

if they set themselves in motion

they drag me along

I fall

I carry [bear] two worlds in me

but neither is whole

they bleed constantly

the border runs

through the middle of my tongue

I joggle it like a prisoner

the game on a wound

Zafer Şenocak, Untitled, Der Deutschunterricht 46 (5), 1993 (see Vallejo 2020).

Second version (Doppelmann):

I carry two worlds within me

but neither one whole

they are constantly bleeding

the border runs

right through my tongue.

Zafer Şenocak, Doppelmann (as cited in Söğük 2008).

A third version I cannot verify, but find compelling:

I have my feet on two planets

when they begin to move

they tear me along

I fall

I carry two worlds inside of me

but neither is whole

they continually bleed

the border runs

through the middle of my tongue

I shake it like a prisoner would

a game with a wound

What is immediately striking is not only the repetition of images — two worlds, bleeding, a border running through the tongue — but what disappears. The titled version, Doppelmann, cuts both the opening stanza (feet on two planets, the risk of falling) and the closing image of joggling the tongue “like a prisoner / the game on a wound”: an image of agitation, compulsion, and a deadly, serious “game.”

What remains in the halved poem is tighter, cleaner, and more legible — but it is also tightly constrained. The poem is no longer allowed to wobble. In the longer, untitled version, the speaker does not simply have a border running through their tongue (the organ that speaks (language), tastes, and articulates truth); they joggle it — an agitated, compulsive motion, out of control – but like a prisoner confined to pacing in their cell, worrying, picking at a wound that will not heal. This restless, embodied unease — this agitated endurance — is precisely what disappears when the poem is split into a more palatable form.

This doubling and halving intensifies the poem’s central tension: the bearing of two inner worlds that never fully cohere, the embodied labor of code-switching, and the impossibility of a complete, unified, individuated subjectivity. The border does not merely separate; it cuts through — through language, through flesh, through the speaking subject.

Reading these versions side by side reminded me of Étienne Balibar’s reflections on Europe as a borderland, particularly his argument that borders are no longer only external lines but increasingly internalized. As he writes:

As a consequence, inevitably, the category of the “national” (or the self, of what it requires to be the same) also becomes split and subject to the dissolving action of “internal borders” which mirror the global inequalities. (Balibar 2009, p. 204)

What matters here is not only Balibar’s ‘diagnosis’ of Europe but his insistence that borders act upon subjects — fragmenting, doubling, and unsettling the very idea of a unified self. The border, in this sense, is not merely geopolitical. It is cognitive, affective, linguistic, social, cultural and emotional.

In his footnotes, Balibar explicitly cites both his own earlier work and Paul Gilroy, and it is to Gilroy that he attributes this line of thinking. Gilroy’s concept of double consciousness, itself building on W. E. B. Du Bois, resonates strongly here — particularly in the shift from Du Bois’s primarily psychological and national frame toward Gilroy’s structural and transnational one. While Du Bois theorized double consciousness in relation to the inner life of the subject and the contradictions of national belonging, Gilroy extends it to describe subjectivities produced across diasporic, imperial, colonial, and global formations, compelled to live across incompatible registers at once. Balibar’s contribution is to frame and mobilize this insight within a European vocabulary of borders, center–periphery relations (à la Wallerstein) and internal differentiation.

In my own research, I conceptualize borders as multiplicity — neither a singularity nor simply a duality. Borders are physical and metaphysical realities at once. They have institutional, cognitive, and emotional dimensions, and they are experienced differently by different people. People move across borders but borders also move across people.

There is an old Chicano saying, often invoked in relation to the 1848 Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo: “We didn’t cross the borders; the borders crossed us.”Overnight, vast regions of Mexico became part of the United States, and many of the people living there became U.S. citizens — without having moved at all.

Identity does not, cannot shift so cleanly.

What interests me most are the feelings that accompany these transformations: the bleeding that will not heal, the joggling, the constant shifting between worlds that may be mismatched, may never feel whole and may never fully belong. How do people make sense of this? How do they live with this?

Perhaps this is a way borders can deepen our human connections — by exposing the arbitrariness of the categories that ground them, the violence of simplification and the ease with which borders dehumanize when they are mistaken for natural facts rather than lived, contested processes.

Leave a comment